Unveiling Ariadne; in the wild terrain of the female psyche

When looking for the wild terrains of the feminine psyche in Europe, we tend to overlook Ariadne’s story. Hers seems to be a tale of the typical forlorn maiden & masculine rescue. But when we shed its the cast iron shackles, we find the roots of a Goddess psychology that supersedes feminine and masculine distinction. Through an inter-disciplinary and multi-cultural approach, the author takes you on a journey of rediscovery and re-imagining, allowing for the emergence of strength and life force both archaic and lively present in modern-day female heroes.

Throughout history, when dominant cultures subsumed others, they strategically employed the native pantheon underneath their own. This proved an extremely successful way to sway entire nations into subordination as belief systems and worship still shaped society. The process of appropriation of mythological narrative is similar to taking a wild landscape and manipulating its ecosystem with a specific use in mind, often by methods of removal, addition, or reassignment. The landscape changes until at one point, its original contours and details have been obscured and we are no longer aware of what lives beneath the surface. Similarly, colonizer cultures integrated stories while discarding or altering those aspects of deities that did not fit into the dominant mindset. In The Masks of God: The Occidental Mythology Joseph Campbell asserts:

“It consists simply in terming the gods of other people demons, enlarging one’s own counterparts to hegemony over the universe, and then inventing all sorts of great and little secondary myths…to validate not only a new social order but also a new psychology.”

For thousands of years, the European psyche has been remoulded by a narrowing of patriarchal rule building layers of landscape that shaped the way we came to view our goddesses and gods, and by extension, understanding our nature in the spectrum of female and male. By both shaving off those layers and by replanting a story back into its original context, its socio-political and ecological environment, we may assign different meaning to how we understand and experience narratives, archetypes, and ultimately ourselves.

Ariadne as patriarchal maiden

The story of Ariadne arises in ancient Greek mythology. Ariadne is Cretan maiden princess and daughter of King Minos. When King Minos disobeyes Poseidon, God of the Sea, by refusing to sacrifice Poseidon’s sacred white bull at the annual ritual, Poseidon curses Pasiphae, Minos’s wife, causing her to mate with the Bull and birth a monstrous horned child. Minos orders to keep this child out of sight and traps him in an unnavigable labyrinth. Consumed by loneliness and cruel treatment by his father, the child transforms into a flesh-eating monster they call the Minotaur. Every year it devoures the seven youths and seven maidens which were sent to it from Athens. One day, one of those seven youths is the archetypal hero Theseus who volunteers for this mission to save his own kingdom on the mainland of Greece. Ariadne falls helplessly in love with him and shares the labyrinth’s secrets. She gives him a flaxen thread, a shining gold, to help Theseus find his way out after he slays the Minotaur. Ariadne joins a victorious Theseus on his journey home only to wake up discarded on the island of Naxos as swiftly as he had wooed her in the first place. After years of despair, Dionysus, vegetal God of Ecstasy and Love, finds Ariadne and makes her his wife.

Ariadne’s myth proliferates in a time when Goddess worship as the central axis of human society is waning. Goddess worship characterizes as a nature-based cosmology in which all of life is imbued with the same cosmic life force carried by the lunar symbolism of the Great Mother’s triple aspect - birth, death and rebirth. The arising pantheon of masculine monotheism stands in the polarizing daylight of the Sun. Anne Baring (2019) describes this period as the emergence of duality in life and death developed into a fear of nature and, somehow, a need to control and transcend it. The human consciousness that begins to break away from its dependence on nature identifies itself with the sun and the sky gods as a solar principle. The solar myth holds within the transcendent light of the divine as the promise of soul’s transmutation, the unveiling of the inner sun, yet it also denotes another kind of myth; the one which turns against the Great Mother and separates light and dark into opposition. In this solar myth that lies at the core of Eurocentric patriarchy, the solar is hero slayer and saviour who must overcome his deepest fears, master the forces of nature, and continuously strive to reach new goals. This is the hero who will give rise to the patriarchal forces that begin to dominate, shape culture and belief systems. It will annex thousands of years of land-based reverie to establish nature domination while relegating the female and exalting the male. Leonard Shlain points out in his book The Alphabet versus the Goddess, how throughout history in Europe and the Middle East, suppression of women’s rights aligns with suppression of Goddess worship.

The Great Goddess

What makes Ariadne especially interesting as an archetype is that she roots into the soil of Crete, an island of great natural abundance that played a specific role in mythology and history. By 400-500 CE Ariadne is known as princess maiden and lovelorn phantom lamenting her fate. As helpless maiden she became the blueprint for subsequent fables and myths on the feminine, thriving as feeble princess stories who seemed to have no choice but to await a knight’s rescue. This repetitive motive threaded the female psyche into thoughts of powerlessness and false dependency, a form of imprisonment women often voice in the therapy room. But where do the stories we tell ourselves come from? Not everything can be thrown on family and upbringing; we swim in a vast social soup of swirling images signifying unwritten rules, morals and ethics. As in Campbell’s words above, these images are imbedded in mythical narrative, in the bedtime stories we tell our children. The images build on each other to shape the reality we live. Our cognitive ability to create meaningful change co-depends on our ability to move out of these expectations and open up to new narrative, but it takes much less energy to make sense of the world using preconceived images than starting afresh. The gap between what we expect and what is there when we actually look, can be startling. What other story then does Ariadne offer when we step into this liminal space?

A few thousand years before Ariadne turned maiden, she was known as the overarching (Moon) Great Goddess of Minoan Crete. Crete’s Goddess centered civilization of matrilineal descent was known for its equalitarian and peaceful society. It lasted much longer than its neighbouring countries; it carried over into the Bronze Age from the Neolithic while surrounding areas had already replaced the Goddess. Ariadne is believed to have held titles such as ‘Weaver of Life’ and ‘the Potent One’ as a direct descendent of the Snake Goddess. Although this got lost in a baptized Europe that locked the feminine into a passive vessel, we find traces of similar characteristics still pulsating in other cultures. In Hinduism, the feminine as Sakti is the active energy while, Shiva, the masculine principle, is passive. The Sanskrit term ‘Kundalini Sakti" translates as "Serpent Power", both the subtle and vital energy of life. Retracing our steps further down into history, we also find this feminine echoed in the myths of Isis and Inanna. Isis is the active principle both in finding her husband, erecting his penis by sacred magic ritual, finding his body parts when he is cut up by Seth, and embalming him after putting him back together. Through her active principle she re-members him at a point in history when worship of the Solar God began to take over. Similarly, we find Inanna and Ereshkigal’s underworld exchange representing both the passive and active principle, here braided into one by Innana’s death while Ereshkigal births, emphasizing that dark dynamic liminal space of vegetating, incubating and regenerating. Both symbolism and actuality of death as attributed to the (Mother) Goddess was once both revered and feared. It belonged to her lunar aspect in which moon waned and disappeared into darkness to rebirth itself three days later.

As Mother Goddess, Ariadne associates with vegetation, animation, and natural life, but as ‘Mistress of the Labyrinth’ she leads us to the center. The labyrinth symbolizes the underworld, the way to the soul, for in a labyrinth you cannot get lost as all paths lead to the middle, the center, the Self.[1]The way of this path is surrender, typical to the Goddess, and differs from our conquering hero in that the conquering turns inwards. We offer up our own fear to something greater than ourselves. Both the meandering ways of a labyrinth path and Ariadne’s many variations in which she meets death, link her into the later manifestation of Persephone as Queen of the Underworld. Ariadne’s ‘descent’ to the island isolates her from life. In one story she falls asleep and lies next to a guarding Hypnos whose home is the Underworld. In another variation, Ariadne births Dionysus’ child on the island after she is killed, therefore giving birth in the realm of death, much like her predecessor Ereshikhal. Birthing in the underworld is synonymous to a birth of soul.

Ariadne asleep with Hypnos at her side. Fresco from Pompeii.

Downing (2007) motions to look at Dionysus, of whom much more was written down, to know Ariadne better. Dionysus is ‘often called the womanly one’[3], and the one to bring men in touch with their femininity. In embodying feminine sensuality, Dionysus comes to women in their most impassioned moments. He is chthonic phallos, deep and bodily. One of his symbols is the Bull. The Bull as a symbol of fertility belonging to the animistic Goddess stretches back to 60,000 years ago in South African cave paintings and spread its mycelial roots into Egypt as symbol of Osiris and in India to Shiva. Both are two distinct lunar and vegetal Gods known for their connection to the land and animal life. In its first known manifestation, the South African water bovine stood for the omnipotent life force. This also translates as kundalini, chi or mana. Where Dionysus connects man to a primal, relational sensuality, he brings woman into erotic autonomy. Ariadne represents this feminine who lives unafraid of her own sex and sensuality.

The Dynamic Feminine - wild terrain of the feminine psyche

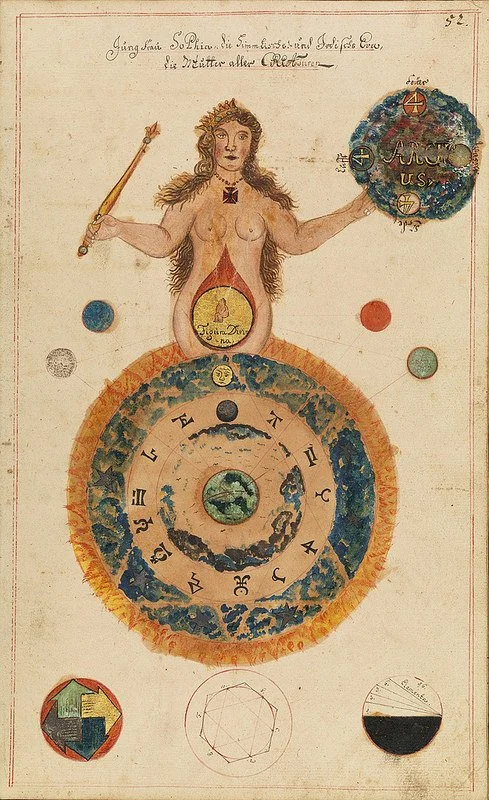

This feminine is dynamic, often associated with untamed lands and wild forests. The dynamic feminine, termed by Jungian theorist Gareth Hill[4] is the realm of wild imagination, the flow of experience, ecstatic embodiment birthed by transformed awareness or chaos erupting out of predictability. The experience of eroticism in the embrace of the Lunar Goddess closely translates to the world as lover, an erotic relationship to the world as found within Hindu culture, early Vedic hymns, but also as the bridal mysticism in Sufism and Kabbalism. This consciousness co-arises in the eroticism of a primal nature of the senses. A bodily shamanic ability to sense and communicate with its more-than-human environment. This consciousness emphasizes the erotic as a relational quality, rather than the sexualization of intimacy. Re-awakening to the world as alive speaks to the ancient Mother Goddess culture that later resurfaced in the gnostic concept of the Anima Mundi, the alchemist term for the Soul of the World. This erotic quality stands in stark contrast to the patriarchal rule which has sought to eradicate this mode of existence by any means necessary.[5]

‘Ariadne’ by John William Waterhouse

Ariadne and Dionysus’ relationship also reveal Ariadne as carrying an androgynous aspect that mirrors Dionysus. The later patriarchal version of Ariadne, the helpless maiden who falls in love with Theseus, will only sustain the promise of the solar hero until she decides to stop waiting for a knight, and picks up her own weapon of choice. A weapon relates to the ability to cut ‘right from wrong’ as a tool of discernment and differentiation. This is what the maiden must learn. Once a woman’s psyche has reclaimed her vitality - vitality meaning life force, but also the sense that one’s actions are meaningfully aligned with a deeper sense of purpose - she has also managed to retract a large proportion of projections onto the men (and women) around her. No longer seeing through inherited perspectives, and embodying a centre of solid stillness within, she comes into her own. She can now withstand, hold and carry through the fertile and the destructive principle of the Great Goddess, the waters of birth and the fire of annihilation, without becoming it. She is active and passive; she becomes the pillar who sustains the bowl of the Feminine, surrendered to a Goddess who does what needs to be done. This face of the Goddess most fierce, best known today as Kali or the Black Madonna as a symbol of the crone,

‘had to be suppressed by patriarchal religions because her power overruled the will even of Heavenly Father Zeus.' She controlled the cycles of life and death. She was the Mother of God, the Nurturer of God, and, as a Crone, the Slayer of God. While Christianity retained the feminine as Virgin and Mother, it eliminated her role as Crone.”[6]

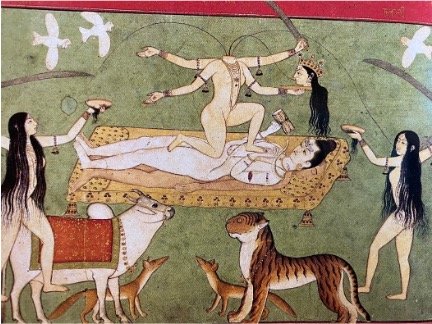

Kali is the final emergence of the great Goddess Durga (Parvati) in her great battle against the demons who, by the desperate plea of the powerless Gods in the face of the masculine demonic, cannot be destroyed by anyone other than Kali. While Kali can also be consumed by her own force of destruction, embedded in her nature lies her relation to Shiva, who in his surrender to her, returns Kali to their unified cosmic dance of life. This type of destruction carries a note of compassion that supersedes the individual in service of the whole, in service of Soul. Such symbolic death as an agent of transformation is reflected by nature’s cycles. Dying in nature is a process of putrefaction and fermentation by yeast and bacteria in which death itself is food for life and rotting matter the cornerstone of a complex ecosystem. After cells have been broken down, decomposing matter starts to purge, a feast for microbials and insects. It soon becomes a hub of activity for all sorts of creatures, and each one links into another. Nothing about natural death destroys relationship; it strengthens it, vitalizes kinship and nourishes the whole.

‘It’s through the Goddess that the creative work is accomplished. She checks the God’s imagination and his creative or destructive mania. She is the intercessor. It is she to whom man must pray. This role of intercession is found in all Goddesses, and even in the Virgin and Christian world. The mother goddess prevalent in prehistoric religions yields gradually to the cult of the lover goddess.[8]’

From Great Goddess to a modern-day heroine: the maiden and the crone

The theme of heroines subverting the antiquated, patriarchal models of the conquering (patriarchal) hero have been surfacing in modern animations of Hayao Miyazaki. Disney has also been changing the narrative of their animus-anima driven plots in the unification of the masculine (prince) and feminine (princess) to favouring the portrayal of independent women as can be seen in Maleficent, Elsa (Frozen I, II) and Vaiana, announcing a new era of a primordial spiritual and psychological narrative. The young women in these stories are feminine and have an androgynous aspect. They require no partner, because they are of themselves, embodied enough to face and receive the Goddess archetype. These women are focused, independent and strong, just like prepatriarchal Ariadne. Their journey requires them to overcome patriarchal constructs that would otherwise overpower them. Although they are challenged to conquer, this ‘battle’ does not require them to kill but rather reabsorb aspects of themselves through uncovering truth, being resilient, intelligent, and reintegrating their instinctual selves and spirit, while surrendering to the call of the unconscious and the feminine dynamics of a labyrinth path. They offer compassionate understanding to their protagonist rather than seeing them as nemesis who needs to be murdered, while also standing firm and unmovable in their convictions of what is right. Convictions that root into humanitarian and ecological justice. We see this arising in the organic and fluid uprisings of young people’s revolutions in different parts all over the world, many carried out by young girls and women. They seek to destroy ideas in order to liberate life. The Indian and Tibetan Ucheyma, a self-decapitating goddess belonging to the lineages of the tantric Buddha Vajrayogini, shows this embedded strength within the feminine who cuts off her false ego for the sake of life. She feeds the world with her blood.

Kangra School, c 18th century, gouache on paper

Throughout the journey, the leading figures of feminist animation are initiated into a deep listening; an ecology of soul that includes the more-than-human world. Their lysis is not to reconnect with a male counterpart, their path weaves the masculine in. Rather, the story leads to a re-seeding into the feminine ground of the Anima Mundi. In these tales the young women are chosen by the Goddess. This choosing by the Goddess does not reflect a singling out of an individual, but more so the relentless and active component of a Goddess who keeps calling, as has often been ascribed to the gnostic Sophia, and the meeting of that calling. She called out to them, and the women responded, however long the journey. We somehow divorced ourselves from this relationship. In the lived reality of patriarchy, Ariadne’s time on the island represents the feminine in deep pain at the loss, not of Theseus, but of her bull brother, and in extension a chthonic way of life. Ariadne’s complexity in her representation of the rise and fall of Feminine consciousness reveals itself more clearly when we look at her actively choosing her fate: it is Ariadne who gives the thread that weaves Theseus into the narrative. Her choice to do so culminates in her own abandonment, leaving her stripped of her ability and strength to find her own way back. By helping Theseus slay the Minotaur, it seems that Ariadne conforms to the ruling patriarchial collective and betrays her own chthonic nature. She denies her body and the earth as sacred and alive, the earth as Anima Mundi. This pain of both abandonment and abandoning feel very much at the core of our human drama, in both men and women, yet there might still be more to Ariadne’s story than this.

Seeding wisdom in times of great need

While Ariadne’s essence as Great Goddess got covered over by layers of patriarchal history, in the archetypal world, we can only bury seeds. Seeds possess the ability to remain dormant in the soil until the right environmental conditions prompt them to germinate. This is how a long-established farmer’s paddock, once shaved from its topsoil, may reveal a field abundant with wild orchids. But the orchids disclose themselves not wholly the same as its parent plant. Seed dormancy is ancestrally initiated by spreading embryos unfully formed and regulated as a responsive process to a changing environment. The capacity of seed dormancy serves as an evolutionary womb for seedlings, establishing itself to be key for subsequent plant diversification.

Ariadne is an ancestral plant of the Feminine rooted in the wild terrains of the animist mind that once lived in Europe. The repeated attempts throughout history to usurp Goddess worship and her inherent feral power started around 6000 BCE. While Ariadne stood firm as a lone surviving Great Goddess in the basin of Old Europe and the Middle East, patriarchal forces ravaged her shorelines, hacking into the rocks that upheld her. Their slaying swords did more than murder a way of life, it was a far reaching sophiacide. When Ariadne made the choice to help Theseus, she abandoned her own story, but did she not also do so because she intuited that patriarchy would last? Did she sense her environment like the plant whose anticipatory action to spawn dormant seeds serves the survival of itself? Perhaps where Ariadne truly reveals herself as a Great Goddess is exactly here. In her act that confirms she is the one who embodies gnosis, a cosmic wisdom of the soil. She is needle, thread and scissors stitching destiny into our reality. Part of Ariadne knew she had to weave Theseus into the story so that he would abandon her, allopatrically separating her, allowing her to remain dormant and resting in the hopeful risk that she would someday form anew. Since then, many fairytale maidens have been put to sleep by the dark feminine - that potent witchy crone - both of whom used to reside in the same Goddess. But today, nap time is over.

[1] Downing, C (2007) The Goddess, mytjhological images of the Feminine, iUniverse, p. 63/64

[2] idem

[3] idem

[4] Gomes, M & Kanner, A (1996) The Rape of the Well-Maidens in Ecopsychology ed Roszak, Gomes & Kanner, p.119

[5] Idem page 120

[6] Woodman and Dickson (1996) Dancing in the Flames, Shambala, p.134

[7] Mokerjee, A (1988) Kali, The Feminine Force, Destiny Books, p61

[8] Daniélou A (1992). Gods of Love and Ecstasy. Inner Traditions / Bear & Co. p. 78

[9] Vaughan Lee (2016) Spiritual ecology : The Cry of the Earth, The Golden Sufi Center

Abram, D. (1996). The spell of the sensuous: perception and language in a more-than-human world. Vintage Books.

Aizenstat, S. (1997). Jungian Psychology and the World Unconscious. In: A.D. Kanner, M.E. Gomes andT. Roszak, eds., Ecopsychology : restoring the earth, healing the mind. San Francisco, Calif.: Sierra Club Books, pp.92–99.

Baring, A. (2019). The dream of the cosmos : a quest for the soul, Archive Publishing.

Baring, A. and Cashford, J. (1993). The Myth of the Goddess, Penguin UK.

Herschkowitz, H (2019) Vision Magazine Jungian Analysis of Frozen 2: How Disney's Frozen II Reveals the Shift of the Collective Unconscious

Jung, C.G. (1973). The collected works of C.G. Jung. [online] Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press. Available at: https://vdoc.pub/.

Lerner, G. (1986). The creation of patriarchy. Oxford University Press.

Macy J (2021) World as Lover World as Self, Parralax Press

Roszak, T., Gomes, M.E. and Kanner, A.D. (1997). Ecopsychology : restoring the earth, healing the mind. Sierra Club Books

Williams, B (2021) Rewriting Ariadne: What is Her Myth?

Willis C, Baskin C, Baskin J , et al (2014) New Phytologist: The evolution of seed dormancy: environmental cues, evolutionary hubs, and diversification of the seed plants

Woodman, M. and Dickson, E. (1997). Dancing in the Flames : The Dark Goddess in the transformation of consciousness, Shambhala.

Evolving into Ecopsychology: the psychology of relationship

Contemporary Jungian psychological practice largely centers on the consideration of the human psyche rather than the ecology of life. The importance of therapy as a service to life and a celebration of interdependent relation with each other and the more-than-human world roots into ancient belief systems and esoteric practice, but seems to have gotten lost in the therapy room. What makes it so vital to return to these roots with the knowledge we have today?

While the image of a living Earth has been kept alive in most Eastern and native traditions, in Europe it disappeared. It was only a small pirate band of hermeneutic Gnostics who kept this secret alive through their alchemical works. In dungeon laboratories, they secretly worked to retrieve the light in matter from the Anima Mundi, the Soul of the World. The concept of the Anima Mundi contained the human psyche as fully entwined with its surroundings, and inherently part of the whole. But at one point, this too got lost in the murderous sweep of religious fervour and the nature caging Age of Reason. In the early 1900s, psychoanalyst Carl Jung retrieved alchemical manuscripts and found in them the archetypal symbolism of the human psyche labouring new consciousness. Jung, in his later years, emphasized the importance of the Anima Mundi, considering the self as ‘embracing the whole universe’ the real mystery of life and what it means to be an awake human being. Jungian psychology and Carl Jung should not be considered as one and the same thing. Contemporary Jungian psychological practice largely centers on the consideration of the human psyche rather than the ecology of life. The importance of therapy as a service to the Anima Mundi seems to have gotten lost in the therapy room. Sufi mystic Vaughan Lee offers the same thought, that the self- care aspect of therapy outweighs its original purpose; therapy needs to be given back to the Anima Mundi.[1] What makes it so vital to return to these ancient roots with the knowledge we have today, especially in a therapeutic environment, and what might that look like?

In this current time, we stand at the pinnacle of worldwide ecological devastation and humanitarian crisis, and for the first time in history, this is happening at the hands of humanity. This era has become known as the Anthropocene; a human dominated epoch that marks a fundamental change in the relationship of humans and Earth, one characterized by extraction, mechanization, and control. Leading up and into the Anthropocene has been the domination of a patriarchal systemic structure. The word patriarchy has been used to mean as ‘dominated by men’, but I use the word patriarchy as a force of archetypal destruction as a will to power that finds expression in both women and men. This force represses the value of relatedness by denying the sacredness inherent to matter, out casting matter as devoid of the divine and thereby repressing the chthonic masculine and feminine principle. In its outward expression, patriarchy flourished from the rise of the solar principle as the transcendent divine and proliferated monotheistic religion, pushing rationalism, mechanization, and control to the forefront. With a Goddess centered culture on the decline, patriarchal rule repressed women while desacralizing nature and the way of the natural. Jungian literature, mysticism and native wisdom describe this one-sidedness of the world around us as a reflection of psychic disproportion and spiritual disconnection. But now, the image of a living Earth seems to be given back to the Western mind.

The dirty truth: an interdependent reality

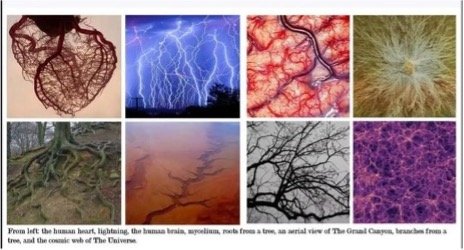

Where our consciousness once separated from an organic experience of life lies the festering wound we tend to band-aid as quickly as possible, but leaving the internal tissue exposed allows it to become the crack through which the light gets in. It contains the ego’s selfish pursuit of individualism with its lust for power and greed, but also the memory that we are a dependent and symbiotic creature, down to the very making of our cells. In biology, no organism lives in isolated purity. We are a contaminated cosmos. We are of the soil, and soiled. It is our ‘faulty’ nature that conduits the miraculous. Billions of years ago, the absence or shortcomings in cells evoked a merging through some form of symbiosis, creating entire new species and abilities. Ancestor algae crawled onto dry land to become the plant life we know today because fungi rushed to their aid, serving as their root systems for tens of millions of years until plants learned how to ‘stand and walk’ by themselves. As Merlin Sheldrake notes in his book Entangled Life, on both the microscopic and macroscopic, the history of life turns out to be full of intimate collaborations in which the idea of ‘self’ can shade off into otherness gradually. The human body even consist of more bacterial cells than human cells. Most of these bacteria live in our digestive tract, our gut and intestines. When we speak of 'gut instinct' as a form of primal, intuitive wisdom, who is doing the talking? To return to these most basic facts and fluid notions of how and what makes us, is also a return to the roots of hermeneutic alchemy. Alchemy praises the putrefied. Fermentation becomes a celebration of the soul. When this becomes physical, when depth psychology becomes dirty, we open into ecopsychology.

Ecopsychology is the psychology of relationship and relating itself. It incorporates the alchemical principle of ‘to awaken to the Anima Mundi, is to awaken the Anima Mundi herself’ thereby embedding all matter with consciousness. Spiritual ecology as a holding space for ecopsychology is by nature an embodied experience, both pulled down into the soil and sprouting up from the chthonic earth into ordinary life. It extends out into the vast web of life and roots into local ecology and community. Stephen Aizenstat (1995) offers the term ‘world unconscious’ instead of collective unconscious to include ‘all creatures and things of the world’ to possess ‘intrinsic unconscious characteristics – subjective inner natures.’[2] This coincides with a shamanic worldview in which the human experience is part of a larger- than-human life, including all life.

David Abram (1995) in Ecopsychology describes the role of the rural Balinese shaman, djankris, as mediating the inner and outer worlds to reestablish harmony as its primary aspect. From here ‘healing’ may occur. ‘

Disease, in most such cultures, is conceptualized as a disequilibrium within the sick person…..commonly traceable to an imbalance between the human consciousness and the larger field of forces in which it is embedded…..Any healer who was not simultaneously attending to the complex relations between the human community and the larger more than human field will likely dispel an illness form one person only to have the same problem arise (perhaps in a new form) somewhere else in the village…. The medicine person’s primary allegiance, then, is not to the human community, but to the earthly web of relations in which that community is embedded.’[3]

Abram (1995) emphasizes that this 'larger field of forces’ has been ascribed to the supernatural in the West, while that which is viewed with great awe and wonder in most indigenous cultures, is nature itself. Recent research on the extensive mind of the spider shows cognitive capacity to extend far beyond its brain, down into its body and even showing the web threads and configurations to be integral parts of its cognitive systems[4].

A reciprocal dialogue

The way of the natural is a reciprocal dialogue; it serves as the vital pulse that keeps the blood flow between the worlds alive. But this is not a tit for tat situation. Reciprocity doesn’t wait for a fair transaction, it believes in connectivity itself. It means being open to the myriad of more-than-human voices which will help navigate our action into nature stewardship. The path that leads into such conscious participation with life, with the Anima Mundi, is a path that bridges the inner and outer worlds. A Jungian analyst prone to embodying such experience can breathe new life into the shamanic aspect at the core of Jungian psychology. It beckons the question; what would depth psychology look like if replanted in an ecocentric worldview, instead of an egocentric one?[5] What if we wed our wounds to nature, embed ourselves in the relationship intrinsic to us? We may come to realize it’s not about us.

Practically, one of the things it might change is the way depth psychology utilizes mythology. In Jungian psychology, mythology is predominantly applied in written format and examined for its psychic content. The oral storytelling of myth however, used to be the pinnacle of matrilineal ancestral society carrying belief systems and practical Earth wisdom. It is still the most effective way to store and convey information spanning thousands of generations. Stories were informed by dreams, ecological and cosmic landscape, social and political structures. Rooting mythology back into its original context reveals how stories speak of our place in the cosmological order and shine a light on archetypal figures not only for their psychic content, but for their specific connection with practical modes of life and natural phenomena. The newly arising discipline of geomythology partly addresses these aspects of mythology. Looking at mythology ecologically can help us relate into the stories nature tries to tell us each day.

Reweaving mythology and its wider biodiversity into depth psychology speaks to the unconsciousness embedded in the multiplicity of the Anima Mundi. While working with mythology and being open to its ecological wisdom, the unconscious responds. This mode of meaning stretches into the practicality of the light in matter, or the lumen naturea. The light of nature which guides us to know when to use which herb for what practiced by shamans, herbalists, and medicine people the world over. Many people working with nature in this way speak of an attunement with the inner worlds through the heart, an empty mind and bodily awareness.[7] I recognize this when working in the garden, sensing what needs to stay or go, receiving a dream that tells me to free up a rose bush, or foraging for mushrooms not by looking, but by responding with my intuitive senses. While working with mythology, I have received practical solutions to garden queries related to the nature of the archetype. An example is an image I was given on the existence of a mist catcher, and how to make it, while working with the fertility and water God Osiris. When revisiting mythology in both psyche and soil, it also frees us from an endless circle of Western-based pathologizing. A mother-complex from an eco-perspective can translate into feeling our own abandonment from ‘mother nature’ as an integral aspect of Self, and the pain nature feels due to us abandoning them.

One of the mycorizzal roots of ecopsychology, ecofeminism, speaks to the connection between ecology and human behaviour, specifically focusing on how forces of domination that despoil the earth and subjugate women are intimately connected. Gomes and Kanner (1996) ascribe to feminist theologian Catherine Keller’s term ‘separative self’ instead of separate self, because the latter cannot exist as we are all interdependent beings. The fight against this biological fact and esoteric truth is what creates the separatist self; ‘an ego armoured against the outer world and inner depths.[8]’ When we acknowledge and live our inbuilt dependence, reciprocity flows freely. Feminist ecopsychology equates the maturation process as moving towards greater complexity in relationships, differentiating between those that foster growth and those that bind people into restrictive predictable patterns. Individual empowerment derives from shared greater awareness. By unshackling the inner and outer patterns of domination and control we can define relationship more inclusively thereby opening up new spaces of connection on the inner and outer planes.

Nature is a family ecosystem

When we treat nature as family and systemically include nature as part of psyche, as a relation that carries as much weight as our human kin, we can invite nature into the conversation as we do mother and father relationships, or partner and sibling dynamics, as standard practice. The word ecosystem etymologically even derives from the Greek oikos, meaning "home," and systema, or "system." We can speak to specific memories, relationships, and experiences throughout life. We can explore time in nature, and the impact of us on our direct ecosystem and vice versa. How does the landscape that surrounds us imprint on us? How do nature beings utilize our consciousness? We can explore old or new modes of being with nature, while being open to the ecological symbolism in our dreams that direct our attention away from our personal psyche into the many voices of the living world and their needs, both as client and analyst. If we take Einstein to heart when he said ‘when you look deeper into nature you will understand everything better’ it can help us open up to each other as well. Through resilience ecology we learn that any landscape is better equipped to withstand natural disasters and climatological pressure if rooted in greater biodiversity and more interconnectivity. Therapy can embrace the techniques of liberation psychology and the need for decolonization that speaks to our collective societal structures as endemic to the individual problems we face. Instead of pathologizing our individual ‘issues', we can extend into group dialogue and offload into a collective dynamic that is part of a systemic imbalance and needs to be addressed as such. Dialogue may then lead to constructive action.

It is high time we bow down to a mentorship by the more-than-human world and view ecopsychology as much as a response to the need of the time, as a voice from the depths. If anything, nature shows us that we need to drop below our striving for individuality and even individuation, down into the underworld reality of symbiotic interdependence and relationship.

[1] Vaughan Lee (2007) Audiorecording, Golden Sufi Centre

[2] Aizenstat, S. (1997). Jungian Psychology and the World Unconscious. In: A.D. Kanner, M.E. Gomes and T. Roszak, eds., Ecopsychology : restoring the earth, healing the mind. San Francisco, Calif.: Sierra Club Books, p. 96

[3] Abram, D (year) The Ecology of Magic, p 304-305, in Ecopsychology

[4] Yaypyassu & Laland (2017) Extended spider cognition Animal Cognition 20, 375-395

[5] The question is put forward by Aizenstat, see note 2.

[6] Joe Cambray lecture (2022) Towards a 21st century model of the Psyche for The Guild of Pastoral Psychology, online

[7] Wolff, R. (2001). Original wisdom : stories of an ancient way of knowing, Inner Traditions

[8] Gomes, M & Kanner, A (1996) The Rape of the Well-Maidens in Ecopsychology ed Roszak, Gomes & Kanner p119

[9] Baring, A. (2019). The dream of the cosmos : a quest for the soul, Archive Publishing.

[10] Chief Oren Lyons (2008). Listening to Natural Law. In: M.K. Nelson, ed., Original instructions : indigenous teachings for a sustainable future. Bear & Company.

[11] Lerner, G. (1986). The creation of patriarchy. Oxford University Press.

[12] Sheldrake, M (2020) Entangled Life, Penguin random House

Through the Gates of Inanna: birth as feminine initiation

When the rhythms of nature show itself through the underworld tidings, its wisdom often speaks through the labour of suffering. This is where, through the weavings of the Crone, the Maiden and the Mother, symbolic death births new consciousness.

Inanna’s mythical journey into the underworld to meet her sister Ereshkigal is a tale of reclaiming feminine instinctual wisdom. A wisdom that once belonged to the worship of the Goddess as the central axis of human society. Around five thousand years ago, at the time of Inanna’s myth, humanity entered into a slow phasing out of this knowledge eventually leading into a global severance of human’s spiritual relationship with Earth and body. This is the story we live today. One way to begin to return to the chthonic wisdom that lies buried in the living lands, our bones and our blood, is through the timelessness of Inanna’s myth whose story serves as an obsidian mirror upon which we might see our own dark sister reflected, and embodied. This is where symbolic death births new consciousness.

When the rhythms of nature show itself through the underworld tidings, its wisdom tends to speak through the labour of suffering. Women in child labour will often experience that when the process of birth shifts from opening the cervix to moving through it, most of the pain subsides. In mythology, it is the opening of the doors to the underworld that brings the initial suffering. In Inanna’s mythical descent there are seven gates to pass before she completes her descent into the underworld. At each gate the gatekeeper, Neti, beats and strips Inanna of her clothes and jewellery.[i] When she finally arrives at the gloomy queendom of her dark sister Ereshkigal, Inanna crawls on all fours wearing only the dirt on her skin.[ii]

Prima Materia

Inanna’s stripping down at each gate represents the grinding down of the false ego. The mill of the underworld will keep churning; it empties those who knock on its door from all false images to the base ingredient, the prima materia. The prima materia is that which we personally and collectively have repressed; here a primal instinctive animal self which reclaimed provides rich soil for the emergence of a meaningful, diversified consciousness steeped in the immanent.

It seems that this churning is what the contractions do in birth before it moves into the ‘pushing’ phase. Most women experience it as painful, an excruciating gut-wrenching horror at the most, or at least as intense. I have heard women describe it as glass shattering in their backs. My first birth literally floored me.

During the initial stage of contractions the womb is physically opening a gate and it takes as much strength to open a gate as it does to keep one closed. The womb is the strongest muscle in a woman’s body, keeping the cervix shut to safely carry a baby whose average weight at the end of nine months will be 3,3 kg. Add in the placenta and amniotic fluid, the womb holds another 1,5 kg.[iii] By the end of those nine months, the force with which the womb contracts, creates a dynamic change in woman herself. She has now become the vessel for the womb. Some call it true labour, when contractions last up to 90 seconds every four minutes or so. To hold this force of nature, to be a vessel for it, may require all the capacity you can find in yourself.

When I was pregnant in 2014, I did not think of this. I watched and read all these wonderful stories about orgasmic tantric birth and quickly decided that that was the birth for me. I made all the preparations to facilitate a cosmic experience of birthing bliss feeling confident I too would enter womb Walhalla. We ordered a home bath. I had a birthing ceremony. There were candles, incense, wind chimes and Tibetan singing bowls. We did tantric breathing exercises, hypnobirthing, perineal massage, and acupressure. At ten pm my waters broke showing blood. I ended up in hospital and forcefully pushed out my daughter seventeen hours later while being hooked up to an oxytocin drip.

That long night, morning and early afternoon, each contraction pulled on another tightly wrought string of feeling abandoned, scorned, attacked, misunderstood, victimized, and overwhelmed. Throughout most of those seventeen hours, I felt like a wounded animal, and acted like one too. I did not experience bliss, only temporary relief. Just like Inanna who demanded entrance to the underworld, a realm outside her jurisdiction, I too had demanded an experience that wasn’t mine to command. All I could do was endure.

In birth, the increasing strength of contractions is the labour of initiation.

Although I thought I had prepared as well as I could have, no one can fully prepare for initiation. You’re not meant to. It is supposed to overwhelm so it can blast away all the congealed misconceptions. If there remains too much familiarity for the ego to hang onto, it will hold the lid on the unconscious, burying both our trash and our treasure.

The physical pain and exhaustion that we experience during labour push us into the deep. The physiological aspects of labour illustrate how pain and exhaustion wear down our mental capability. We move into our primitive brain and constellate a flight or fight reaction exhibiting emotions of anxiety, panic, stress, and fear. In Jungian terms, you could also define this as an encounter with the shadow. The typical shadow shows itself in our reactions as primitive, instinctive, fitful, irrational, and prone to projection. It is our dark side, that which we do not want to be nor accept about ourselves, but this can be both something we view as negative or positive. During my first birth, what I experienced was the opposite of what I had ‘envisioned’.

Before we continue with Inanna’s journey, we must take into account that Jungian psychology and thought stems from a Western mind raised in a euro-patriarchal landscape. A person having grown up in a differing cultural setting might have a different experience of shadow and what it constitutes. But for psyche to mature in any culture, there will be a ritual, practice or theory in place to serve the need of both being peeled to the core and opened up into new layers of consciousness.

Inanna on clay tablet also known as Ishtar (Mesopotamia c 2500-3000 BC)

Inanna and Ereshkigal: the chthonic feminine

In Inanna’s story, it is her sister Ereshkigal who personifies the shadow. She is the Queen of the Underworld. Inanna had decided to visit Ereshkigal to attend the funeral of her sister's late husband, but Inanna indirectly caused his death at the hands of her own pride. Visiting the underworld brings her literally and symbolically to her knees so she may face Ereshkigal, her own shadow, surrender to the wisdom of soil and reintegrate her instinctual self. This myth arose at a time when polytheistic Goddess worship as the central axis of human society was waning, and monotheistic religion arose with a focus on the one male God. With the dawn of a male God centred belief system, so did the focus shift towards reason and logic, eventually separating the sacred from soil, intuition, sexuality and the chthonic. Inanna represents the feminine turned away from its sacred ground of being. Her story shows us what it takes to find our way back into a holy dialogue with our own body and the way of the natural. She is there to guide us into the depth of birth as rebirth.

When Inanna crawls towards her sister’s throne, Ereshkigal casts Inanna the eye of death and has her lifeless naked body hung on a hook.[iv] Such symbolic death is indispensable for spiritual life and must be understood in relation to what it prepares; birth to a vaster mode of being.[v] As Inanna’s flesh rots away for three days, something remarkable happens. The ego-self represented by Inanna becomes subservient to her shadow sister Ereshikgal, and not without conscious intent. Before Inanna made her descent, she had instructed her consort Ninshubur to call for help if she were to stay away for more than three days. It illustrates a knowing of the underworld tidings and its obscure process of gestation. The killing of Inanna can then be seen as the choice to submit to the organic wisdom of nature. In the rotting of her flesh, Inanna is consumed by the fermenting processes of death. Fermentation converts raw materials into a desirable product that sustains new life. Here Inanna’s body as raw material, or prima materia, is transformed into something useful, into new consciousness. The process requires an active passivity of the ego-self and a submission or acceptance of life ’s circumstances as it is presented in the moment. Instead of fighting whatever comes our way, we heed to the call of the underworld and let it shape us, let it birth us. In this moment of submission, the shadow performs the active role of birthing something anew. As Jung says:

We must…..let things happen in the psyche….This is an art of which most people know nothing. Consciousness is forever interfering, helping correct, negating.” (C.G. Jung 1958, as cited by Lowinsky 2016)

While Inanna’s corpse decays, Ereshkigal goes into labour. She leads the way into new life. This is feminine destruction with the purpose of creation, fundamental to the workings of the crone energy that stands firm at each threshold of feminine initiation. Woodman and Dickins (1996) describe this energy as “the Goddess who gives life is the Goddess who takes life away. . . . we hold the paradox beyond contradictions. She is the flux of life in which creation gives place to destruction, destruction in service to life gives place to creation.’[viii] The crone lends her helping hand and discards us, testing inner faith; a yielding to build endurance, which allows us to know our true strength and from a healthy ego-Self relationship, surrender more.

Death and Rebirth: a mythology of initiation

The psychology of initiation finds its roots in these death-rebirth myths, where the archetypal processes of death and resurrection can be utilised in the task of transformation[ix]. In almost every ancient culture you can find a myth of the dying-and-rising God. Isis and Osiris, Persephone and Inanna, but also that of Buddha and Jesus. The death turns into birth story ‘corresponds to a temporary return to the primordial Chaos out of which the universe was born, while ‘rebirth’ corresponds to the birth of the universe. Out of this symbolic re-enactment of the creation myth, a new individual is born.’ (Eliade, 2017)[x] The rituals that re-enact this great shift in cosmic order as a reflection of a shift in consciousness are mainly lost to us. In the West, we are mostly dependent on nature and life to shock us into maturation. Childbirth presents an opportunity of not only initiation, but also one to enter consciously - to a certain extent. You can either work against the tide or go with it.

Where the tide takes you may neither be relevant nor redundant. One of my clients’ wishes for a natural birth took on a different meaning as we explored her dreams during her pregnancy. While she hoped for a birth without medical interference, she also expressed a need to be in the hospital as it made her feel safe since it was her first child. As we worked with the images of the unconscious, she relaxed into the wisdom of her own body and in the medical knowledge of the hospital. She expressed her wishes as much as she could, and as she did so, dream images of a horse surfaced. In our last session together she was more than a week past her calculated due date. We worked with the image of the horse, feeling its strength, walking and standing as the horse. She experienced its clarity while feeling grounded in her body. Her waters broke as she motioned out of the experience. A week later she recounted her story to me. The birth was long and arduous because the cervix did not dilate. When her gynaecologist asked her if she wanted to continue natural labour, she felt herself connect into a clear mode of thinking, much alike she had experienced while connecting into the horse. She gave in to what her body told her and asked for a caesarean. As they wheeled her into the operating room, she not only felt present in herself, but surrendered into the loving arms of the four women helping her and her partner beside her. She describes the birth of her daughter as miraculous, loving and gracious. She could not have imagined that a caesarean birth would feel so natural. She had surrendered to the tide.

For the birth of my second child, I made similar preparations to my first. We hired a birthing pool, a friend mixed herbals and tinctures. I watched videos with my daughter and reacquainted myself with hypnobirthing. I performed rituals, received massages, and I took the time to ease into my body. But I didn’t do it with a singular idealistic focus in mind. Pain creates muscle memory and endurance builds character.

This time, I merely followed the currents of my instinct and my dreams as they entwined into consciousness.

Looking back, I watched hypnobirthing videos because my mind needed to know what my body was doing so that when I was in pain, I could marvel at the brilliance of nature’s design instead of sliding into victimization. I watched birth videos with my daughter, both the relaxed ones and those of women screaming in pain, because I wanted both of us to be prepared for birth as it is and as it can be. I went to a massage therapist, because I needed to be touched and my husband simply did not have the time to do it. It was on the massage table that I felt my body become Earth, my thighs her hills, my blood her water. My body was hers and the birth of my daughter my gift back to Her. From that moment, it wasn’t just my experience anymore, it was Her experiencing through me. I honoured the Goddess through ritual, but mostly by honouring her dark chthonic, earthy wisdom. By ‘getting out of the way’ just as Inanna had to when her corpse was flung dead on a hook.

It is also here in the story where help from the upper world leads to the rebirth of Inanna. While Ereshkigal endures her labour pains below, Inanna’s consort Ninshubur runs around looking for help above. It is Enki who finally turns up with the goods. Enki is a multifaceted God and holds amongst others the virtues of mischief, magic, wisdom, water, and male virility. Enki is said to be an Earth God, having made a full descent-ascent to the Underworld, and often chooses the path of compassion, forgiveness, and wisdom. At Ninshubur’s plight and with a father’s love for a daughter, Enki scrapes some of the dirt from underneath his fingernails, which become two sexeless beings, or demons, and sends these to Inanna. The beings transform into flies, so they can enter Ereshgikal’s cave unseen carrying both the water and bread of life for Inanna’s revival. The flies on the wall don’t do anything besides groaning when Ereshkigal groans, moaning when she moans.[xi] I have seen this behaviour replicated by my one-year-old daughter in response to her crying elder sister. As the eldest throws herself in primal fits of crying over lost candy or anything she feels a distinct ‘loss’ for, however trivial it might seem to adult eyes, her little sister will come up next to her and echo the sounds while patting her back, until hands reach out for embrace and crying soothes into simmering sobs. In this simple yet unexpected show-up of support, Ereshkigal softens as well and gifts them anything the flies may wish to take. They want the corpse and Inanna finds her way back to the living. It could be argued that in the surrender of the feminine, in the complete softening into Eros, the integrated masculine principle responds. This masculine is in touch with both the earthly and cosmic realms and descends with a clarity of compassion that extracts light from darkness, and paves the way for ascension.

When starting the path down into the initiatory realms of birth for a second time, I passed each gate releasing something. A misplaced ideology, a sense of false ownership, the fear of losing control. But it was in the peak of labour pain that I truly gave in. Giving in not by slumping into self-pity, but by giving into a power much greater than I will ever be able to fathom. The Goddess works in mysterious ways, they say, and the steps that take one from contraction into expansion work differently for each person, for each new descent. She had been leading me, hinting of what was to come, or could be, through a myriad of ways throughout my pregnancy.

I had tiptoed the edge of the inner and outer worlds for months. My brain had become soft and my experience of the world around silenced. This state of being, or birth energy, gradually descends in and around a woman’s body, a serpentine coiling, but with the gentle touch of a cloud. In the last week, my uterus had been kneading the cervix with increasing intensity each day, announcing the onset of labour, but at the last moment subsiding.

“I dream about little elephants walking along a bank. They turn into young children and are accompanied by a sweet but strict elderly woman. Now they stand in the centre of an auditorium shaped spiral. A girl with curly blonde hair runs towards me. We hug each other at the outer rim of the auditorium, so happy to see each other, but it isn’t time yet as the old woman calls her back.”

The next night, our daughter was born.

This is our story.

I tell my husband it could happen tonight. He lays a towel underneath me, just in case. Ten minutes later we hear the muffled sound of a balloon popping. Warm water trickles down my leg. ‘What was that?’ he asks. I giggle as a flood of oxytocin rushes into my bloodstream. “My water broke,’ I reply.

The sequence of events mirrors the first time. Water breaks at ten pm, contractions start immediately. But this time there is no blood.

My husband goes downstairs to set up the birthing pool while I go inside, down into my breath. It feels intense so quickly. I wade in and out of the bath upstairs, finding solace in weightlessness. Nobody records the rhythm of my contractions, only I know, sort of. Although I have learnt to elongate my outbreath to induce calmness, there are moments I want to run away from the pain. I automatically start to groan low tones. It is not something I practiced or read about, it’s what my body wants to do. I remember this from last time and think back to those long seventeen hours while I hear my mother climb up the stairs. She’s been called in to look after our eldest.

My husband welcomes me down two hours later. He feeds me tinctures and warm tea that I hardly notice drinking. The birthing energy amazes me again. How it centres and pools around, creating an even stronger primal instinctual silence as the mind completely fades. The part of me still consciously present condenses into a singular point of focus, I can only just about make out the candlelight and altar. A week before, I received a blessing ceremony here, in this same spot. The drawings of the women hang above the altar, including my painting from a dream experience a year before.

dream image of ‘woman by fire’

Suddenly I am fully aware that I am in another dimension, but not the same as a dream. She is in front of me. A beautiful native elderly woman in a Maria cloak made of fire. She looks powerful in her silence. Not necessarily peaceful, but more of a focused silence, in surrender to this fire. This is necessary, I know, the fire. She is showing me this, that she has to go through this. It all happens very quickly, the thoughts, the experience. The reality of it scares me and I throw myself back into my body. I re-enter through a burning heart, waking up underneath the stars where I am camping out with my daughter.

My husband sits behind me in the pool while I feel hot energy enter my crown. Each time it funnels down into my body, it initiates another big contraction. By watching the videos, I know what my womb is doing, contracting out and up to open the cervix. I don’t do much, rather as little as possible. The wisdom of my body is at work and I am just an observer of something completely magical. Yet every so often the contractions are too much, I cannot bear them all. Especially when my husband pulls away to do the necessary things. Changes, however small, puncture a hole in my bubble. The familiar feelings of abandonment and victimization creep up again. I try to breathe through it, but it has only been three hours. I ask my husband to call our midwife. I want drugs.

With her thirty years of experience, she listens to my moans and concludes I am not yet experiencing any ‘peaks’. “Mindset”, I hear my husband repeat. “Call back in an hour.” Right, no drugs then.

My midwife’s cool and distant words sentence me to the imprisonment of my body. I am bound within its pain and any struggle against it, any notion of being able to cope, now fully disappears. Something in me knows that the only way out is fully in. I have to submit; all of me needs to bow down. Rather than moving or circling, my body wants to be still. I sit myself upright and slide into a heart meditation I have been practicing for the last few years. I feel my husband steady himself behind me, locking into position he won’t move out of until our daughter is born.

My breath sinks into infinity, and almost immediately my perception of pain ebbs away. I fade away. There is only sensation. Energy converting into movement, the opening and closing of my womb while my breath holds me. For thirty minutes I wade into yet another boundlessness that cannot be put into words. Then my body changes gear, she wants to push. In that moment I remember a fleeting image I had of birthing this baby with just us, no midwife present. Having learnt from last time, I had let it go as quickly as it came, but now it seems to be given back to me. I don’t tell my husband about what is happening, I don’t want him to call our midwife. I can do this. We can do this.

The contractions pour through like a waterfall, just as I dreamt a few months before.

“I’m on my way to the hospital to give birth, but the car won’t start. I park and walk outside. A dolphin passes by. She lets me sit on her back. I hold on tight as we plunge down a waterfall. Even though it scares me a little, all I can do is give in.”

I feel her head pushing through. I touch the top of it with my fingers, it feels mushy yet firm. My vagina isn’t ready though, so I let my baby’s head sway back and forth a few times. The force flowing in increases again. I hold onto the bath rail to steady my body so I can allow this torrent to rush through only guiding it down with my breath. With the next push I let her slide to the edge. They call this the ring of fire, the point at which the vulva is stretched the furthest and the longest. I hold her there, waiting, breathing, burning.

The following wave pushes her head into my hand while the next one pushes her body out of mine. I lift her out of the water into the air.

“Huh? Oh, Ohhhh!” my husband gushes. Well, I hadn’t told him…

She lies on me quiet and peaceful. For a moment I worry she is not breathing. My husband notices her umbilical cord wrapped around her neck, so I lower her back down into the water, uncoiling the chord. Back on my chest, he gently blows into our daughter’s face, and she exhales her first breath.

~

Bodhi Mae was born at 2:30AM, on the 17th of November 2020.

~

Note: To explore the depth that pregnancy, birth and early motherhood bring, including the darker periods, analysis can be valuable. I specialize in guiding women through these transformative times.

Bodhi Art by Lotte Hauss

[i] Inanna’s story, Sylvia Brinton Perera, Descent to the Goddess, (Inner City Books, 1981)

[iii] Statistics from babycentre.co.uk

[iv] Brinton Perera (1)

[v] M Eliade, Rites and Symbols of Initiation: The Mysteries of Birth and Rebirth (Spring Publications 2017)

[vi] J Mark, “Innana’s Descent: A Sumerian tale of Injustice” www.worldhistory.org/article/215/inannas-descent-a-sumerian-tale-of-injustice/ (2011)

[vii] Naomi Lowinsky, The Rabbi, The Goddess and Jung (Fisher King Press, 2016)

[viii] Marion Woodman and Eleanor Dickson, Dancing in the Flames, (Shambhala Publications, 1996)

[ix] Eliade (3)

[x] Eliade (3)

[xi] Perera (1)